In the lively comments on

this post, there was some discussion of monetary offset. Mostly for my own benefit I thought I'd go through the monetary offset mechanism and discuss where model assumptions enter. Hopefully, I won't be too off base -- or if I am, it will be corrected in further lively comments.

I made a rather bold claim that monetary offset is at its heart an assumption about the power of monetary policy in a footnote, citing

Scott Sumner's paper [pdf]. I'll use that paper as the primary reference for the discussion here. The assumptions will be titled in bold below, with details after --

Vox-style.

The basic framework for monetary offset Sumner puts forward is the AD/AS model. I'll just link to the

wikipedia page for what assumptions that entails. Here is the diagram from Sumner's paper that I'll refer to a couple times below:

The idea is that the central bank is targeting an economic equilibrium (price level or inflation) at A so that a boost in AD to AD' through fiscal stimulus, moving the equilibrium from A to B, implies that the central bank will tighten (or will be expected to tighten), bringing AD' back to AD and the equilibrium back to their target at A.

AS is unaffected

One assumption in the AD/AS model I'd like to pull out is that AS is unaffected by shifts in the AD curve. A different way of putting that is that the equilibrium point A still exists to return to if the fiscal expansion leading to the shift to AD' occurs.

I discuss the possibility of the original equlibrium A not existing in a different context in a post

here. The assumption of the AD/AS model is that A does exist after the fiscal stimulus and monetary offset.

This is one that I brought up with Sumner in the comments. The "inflation target" part itself doesn't matter so much -- it could be any number of targets or monetary policy regimes. The argument for monetary offset is that the central bank has a 2% inflation target so that when fiscal policy tries to move from A to B, rasing inflation above 2%, the central bank tightens (or is expected to tighten), bringing inflation back to 2%.

The "liquidity trap" shows how this assumption is important. In a liquidity trap, the central bank can't meet its inflation target, say only 1% inflation vs a 2% inflation target. Liquidity is hoarded -- not chasing goods and driving up the price level. If fiscal policy brings inflation up to 2%, then the central bank shouldn't be expected to offset it -- and if it did that would contradict the 2% inflation target assumption.

The monetarist counter to this (AFAICT) is that the central bank was really targeting 1% inflation, not 2% inflation -- i.e. the original assumption that the central bank was meeting its target.

The Concrete Steppes aren't too vast

I think it was

Nick Rowe who came up with the phrase "the people of the Concrete Steppes" to refer to economists, bloggers and commenters who doubted that central banks could manage expectations and give forward guidance to move inflation or output without actually conducting open market operations (or showing what those operations could be) -- taking concrete steps. However, like Sumner's

gold mining company analogy, sure the announcement can move markets, but they have to start producing some gold in the long run.

The assumption here is that the required concrete actions by the central bank are not outside the realm of possibility. To put it more economic terms, the commitments by the central bank are credible. I hope this roundabout way of getting to central bank credibility illuminates the model-dependence of the meaning of credible.

In Nick Rowe's argument, the concrete steps required are assumed to be effortless (humans just change their minds). I.e. the concrete steps are always feasible. Expectations based on these not-incredible steps are assumed to carry us from one equilibrium to another.

In general, monetarists assume any inflation target can be credible (maybe not specific cases -- Zimbabwe might not be able to credibly promise 2% inflation, but theoretically there could exist a central bank that has a given inflation target).

This credibility assumption is one that at least partially breaks down in the liquidity trap argument. As

Paul Krugman likes to say, the central bank must credibly promise to be irresponsible to produce inflation. Monetarists will to point out that the central bank can still credibly produce deflation in the liquidity trap argument, hence monetary offset mechanism in the diagram at the top of this post still applies. Again, this counterargument is based on the idea that the central bank is meeting its inflation target -- a central bank cannot credibly create disinflation/deflation if it is undershooting its inflation target and fiscal stimulus brings inflation up to its target. (Although maybe the ECB really is actually this irrational? Its inflation target is 2% without fiscal stimulus, which it can't meet, and 1% with?)

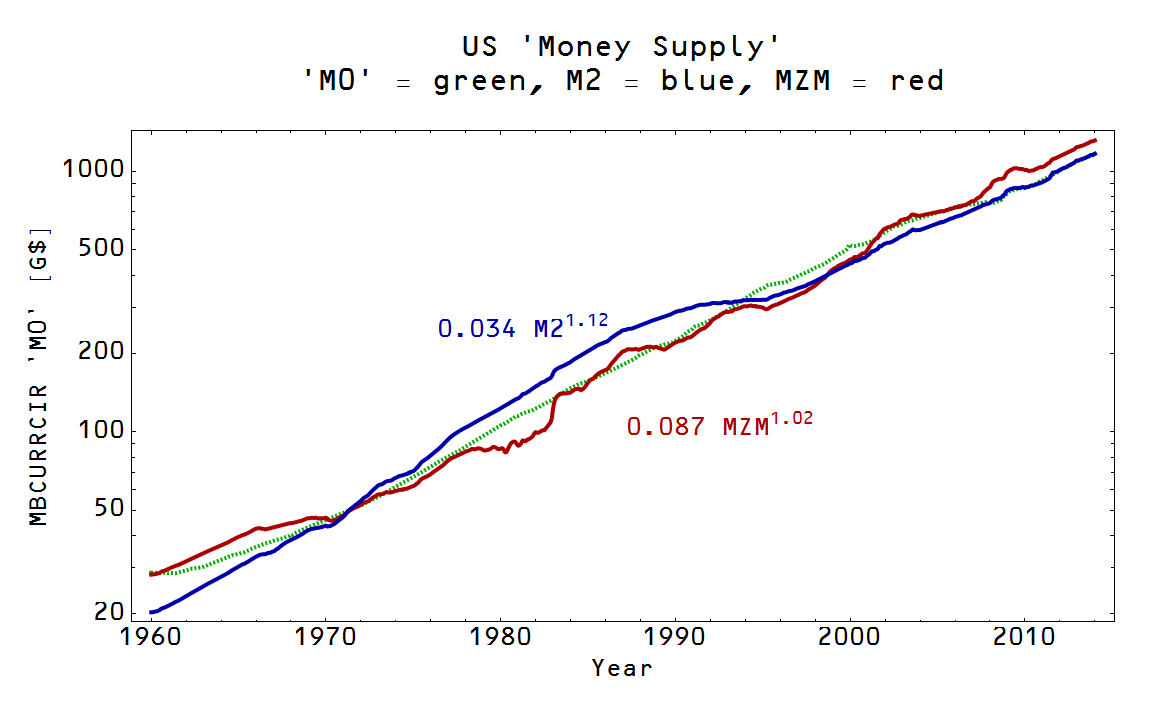

In the information transfer model (ITM), expectations don't matter so much. Regardless of what is expected, the macro variables will generally follow their trends. However the ITM provides an example of the model dependence of credibility. If the monetary base (currency component 'M0') is small relative to NGDP, the assumption of central bank credibility is reasonable. If the base is large relative to NGDP, then some inflation targets may not be credible -- because some inflation rates are impossible in the model. Additionally, the tightening required to offset fiscal policy may be outside the realm of credibility (e.g. taking 10% of currency out of circulation to offset a 3% of NGDP fiscal package, as shown

here). This lack of credibility for given inflation rates applies to deflation as well. The idea is that for some economies,

∂P/∂M0 ≈ 0, so both inflation and deflation can require incredibly large increases (decreases) in the monetary base -- if the target price level is even achievable at all.

One of the things (instruments? tools? this is where the proper technical term should go) central banks use to conduct monetary policy is interest rates. Imagine a budget constrained country with high debt to NGDP; raising interest rates -- considered to be a tightening move by the central bank -- would impact the debt service of that country, impacting the govenment spending package that brought AD to AD' in the diagram at the top of the post. Now the monetary policy required to bring equilibrium B back to equilibrium A is a function of the monetary policy itself! The problem becomes nonlinear and no longer obviously stable to perturbations around the equilibrium A. Additionally, the fiscal impact of debt service can potentially be the same magnitude as the fiscal spending package. In that case, raising interest rates brings you back to equilibrium A without any monetary impact on the price level. This is a bit like finishing building a piece of IKEA furniture and looking back at the box and finding a piece you didn't use.

Before this seems like a just-so story, I'll quote from my response to a

comment by Mark Sadowski:

Debt service in Spain jumped fourfold in 2012 after the ECB rate increase, adding 30 G€ in payments, or about 3% of 1 T€ NGDP. Because of the budget constraints, that meant government spending decreased about 3% of NGDP -- accounting for the entire [observed] loss.

I'm not saying this is the definitive answer. This might not be the mechanism that produced the double-dip recession in the EU -- maybe monetary offset is the real reason.

If there are no concrete steps required and the central bank can always meet its targets, the assumption of small fiscal impacts is less of an issue.

More assumptions?

Potential additions in future updates.

.png)

.png)

.png)